Hard stone carving in the Urals: a story with a new beginning

Hard stone carving developed intensively in the 18–19th century and the active exploration of the Urals — one of the most unusual Russian regions, rich in unique gems — played an important role in this process. The Ural Mountains, which gave the region its name, divide Europe and Asia and behind them lies vast Siberia. Historically, the development of this region has been linked with mining and naturally, such a diverse range of minerals and rocks generated a lot of interest in the art of hard stone carving.

How it all began

The development of the Urals and its cities is closely linked with industry. The 18th century saw huge development in eastern territories, with the construction of new factories and settlements nearby, the discovery of rich mineral resources and, of course, more and more types of new minerals.

By 1726, many self-taught stone carvers were working in the Urals, often aided by European craftsmen. The local artisans were quick learners and made impressive progress in the art of hard stone carving. In 1751 members of several workshops started working at the Ekaterinburg lapidary factory, which was a truly pivotal moment. Within several decades, the local stone carvers mastered numerous methods and genres of stone carving known at that time. Gradually, they started decorating their works with optional (from a functional point of view) elements, and throughout the 19th century, the development of hard stone carving was truly unstoppable; new motifs emerged, carving techniques were perfected and the range of use of stone expanded. Grapes made of amethyst, currants made of obsidian, wild strawberries made of slag — by using the unique textures of every stone, craftsmen learnt to bring them to life.

Several generations of brilliant craftsmen emerged from the Urals and they often received commissions from both Moscow and St. Petersburg. By the end of the 19th century there were more than a hundred stone carving artisans in the Urals.

The heroes of their time

Many people will have heard of Carl Fabergé (1846–1920). Despite the fact that he is mostly famous for the jewellery manufactured by his company, it was he who guided the creation of the first stone sculptures in 1908. Fabergé’s company worked together with the Ekaterinburg lapidary factory. The stone was purchased and samples were commissioned in the Urals, and the local craftsmen were invited to work on large-scale projects. Interestingly, the first figurines in the series of ‘Russian types’ based on the sketches of a guest artist were crafted by local stone carvers from Ekaterinburg. What is more, a stone carving division within Fabergé’s company started with a few craftsmen from the Urals.

The stone carving in the Urals gave rise to a certain number of legends. One of them was based on the life of Danila Zverev (1858–1938), whose level of skill and intuition inspired awe in his contemporaries: people said that he could sense where the deposits of the most precious stones were from far away. Zverev’s efficiency and strong character paid off; by working hard and constantly improving his skills, he became a recognized expert, and provided gemmological appraisal services, gave consultations with famous scientists and received commissions from Moscow and St. Petersburg.

However, the legacy of Alexey Kozmich Denisov-Uralsky (1864–1926) is of even greater interest. He came from a family of stone carvers and inherited his skills and love for stone carving from his father, a miner. Denisov-Uralsky was not even thirty when his works started receiving acclaim and awards both in Russia and abroad, at exhibitions in Moscow, Copenhagen and Paris. He was the first to talk about the issues surrounding mining of stone deposits in the Urals, representing the region at some major events. This stone carving craftsman and artist made an invaluable contribution not only to the development of the art of stone carving, but also to increasing its popularity.

The Urals forging victory

The dramatic effect and durability of stone has always ensured a high demand for stone sculptures and other works of art. During the Soviet era, the national trust Russkie Samotsvety (Russian semi-precious stones) and its numerous members were commissioned to work on a very high-profile project — a mosaic entitled ‘The industry of socialism’, measuring 5910 × 4500. The local craftsmen from the Urals were responsible for cutting segments and grinding stones for the mosaic. No stone works of art of comparable scale have been produced since then.

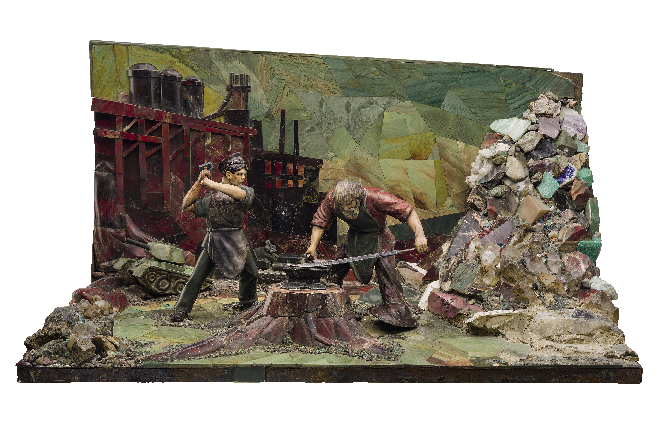

When a new vocational art college was founded in Sverdlovsk, which was later renamed Rifey, it gave major impetus to the art of stone carving in the Urals. Within the first few years, a number of students under the guidance of Nikolay Dmitrievich Tataurov (1887–1959) created a composition called ‘The Urals forging victory’, uniting for the first time a flat and a three-dimensional mosaic in one piece. It portrays the local workers at a factory, and this subject fits in beautifully with the idea of continuity of art and exploration of the Ural’s rich resources.

This is how three-dimensional mosaics became part of the curriculum at the college. However, small stone sculptures were still not as popular as they wanted them to be because of the extremely laborious processes involved. It is not easy to express all the nuances of facial expressions and the details of clothing in stone. Such precise work required hig-quality equipment, a professional approach and mastery of related art skills and disciplines, such as composition and anatomy.

Achievements of the new era

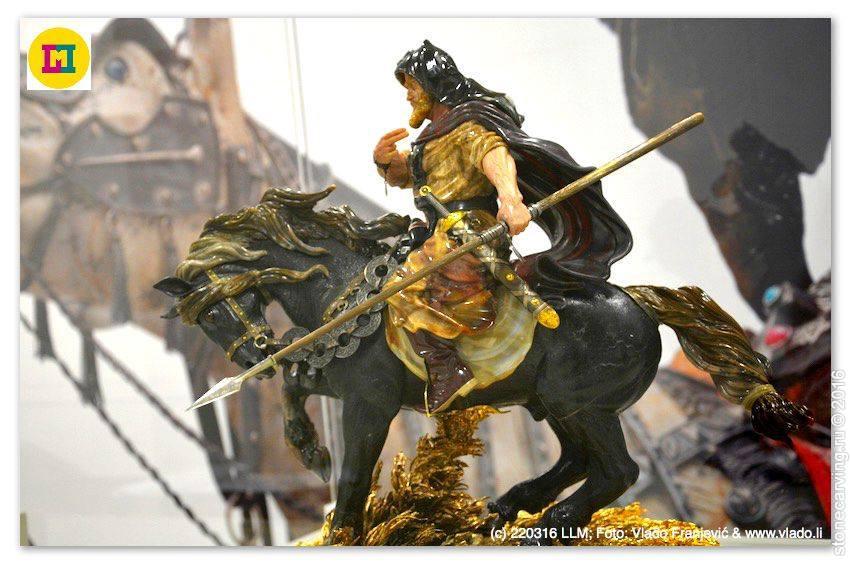

By the 21st century, stone carvers gained access to the free market of stones and minerals and have been actively exploring new stone working technologies, whilst preserving the best traditions of this unique art. You could argue that the Urals has a specific style when it comes to working with stone, which is less likely to conform to and imitate other styles. Now, craftsmen try not only to create a composition with several characters, but also to express their identity through facial expressions, posture and emotions.

This meticulous work has several stages: developing a character, selecting stones, carving the stones in a way that reveals their individual features, creating a mosaic and so on. Craftsmen are developing increasing complexity in both form and substance; static images give way to dynamic compositions with a story, and stone sculptures are growing in size too. However, they are using fewer elements made of jewels or enamel and this ‘stone purity’ has also become a trademark of the Urals style.

A natural artist

Stone is a noble and self-sufficient material, which possesses a certain magic. It is impossible to work with stone unless you have a feel for it and can help others around you feel it too. However, experience gives a special kind of intuition and virtuosity; it is as if the stone itself leads the craftsman, showing him the way around its imperfections, inclusions and irregularities.

This is what makes sculptures made from a single piece of stone so stunning. A piece of stone can give a subtle hint about the potential work of art which it lends itself to, and this hint can only be understood by an expert. When working with a single piece of stone, an artisan first outlines the general shape and then moves on to the details so that the final image becomes recognizable to the viewer.

One of the characteristic examples is the stone sculpture of Pan (p. 186), which is made of several large pieces of carved agate. The craftsman’s meticulous Nand careful work revealed a hidden potential, turning the natural imperfections of the stone into a unique feature. Interestingly, when he was working on the ram, also made from a single piece of stone, he suddenly came across a white lens in the very place where he was planning to carve the teeth, and it was as if the stone animal ‘smiled’. Craftsmen usually have many similar stories to share. Sometimes it so happens that the concept changes halfway through the process. When the work with the stone begins, sometimes a different character comes out, and only a sensitive and careful person can notice this.

Three-dimensional mosaic

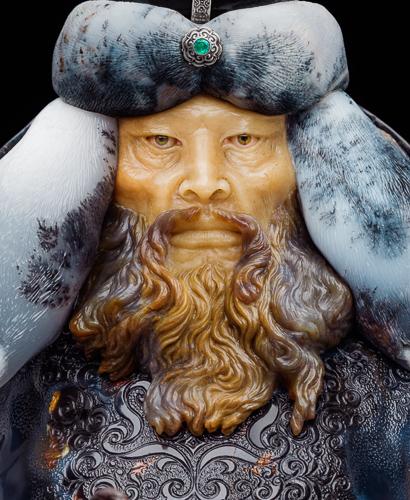

The majority of the exhibits are three-dimensional mosaics. These are small figurines made of several types of stones pieced together. The various combinations of colours and textures open up exciting creative opportunities. Meticulous craftsmanship makes it possible to avoid conventions in stonework and bring the sculptures to life.

It seems that local stone carvers prefer this advanced technique and truly enjoy extending its scope. For instance, they have started working on multi-figure compositions and genre scenes, based on myths and fairy tales. These timeless and truly archetypal images lend themselves beautifully to stone.

When working with a three-dimensional mosaic, the stone carvers strive to ‘fulfil’ the potential of stone in each and every detail. When you take a closer look at the stone sculpture of Koschei (p. 52), you are immediately struck by how true-to-life and convincing his face is. Red veins and tiny cracks on the stone surface are ideal for representing the dry and wrinkly skin of the old and painfully thin Koschei. The nature of the carefully chosen material became a unique means of expression for the stone carver.

Looking for such components and piecing them together in one composition requires a lot of hard work. That is why large-scale stone sculptures are impossible to copy. This is not only due to the complexity of the process, but also due to the unique texture of the stone. As a result of this meticulous work, the viewers see not only a carved mineral or a sketch that now exists in stone, but a complex composition, where all the different elements are balanced and form a single image.

|

|

The exhibition “Heroes. History in Ural Stone Carving” has opened in Liechtenstein

The exposition is displayed in Liechtenstein National Museum

Heroes. History in Ural Stone Carving

The Opening Ceremony of ‘Heroes. History in Ural Stone Carving’ exhibition will take place on the 23rd of March at 19.00 in Liechtenstein National Museum

The exhibition in Liechtenstein has opened its doors

July 9, 2015 — The exposition welcomes everyone in Liechtenstein National Museum until 18 October 2015.

Introduction

Today we are witness to the golden age of new media. Children now turn to computer games rather than reading or listening to audio books. That is probably why this exhibition of stone sculptures based on fairy tales is somewhat surprising. The question that arises is perhaps the following: Is there still a need for fairy tales or for the art of stone carving?

Stone carving: from concept to finished work

Hard stone carving is a truly unique art. On the one hand, the stone carver is an artist and a creator, who gives a hard and shapeless piece of stone a new life and a new shape. On the other hand, his most important task is to unveil and demonstrate what has already been created by nature: beauty, structure and the unique character of the stone. When it comes to working with stone, each piece requires this fine balance between creating and being guided by the material itself.

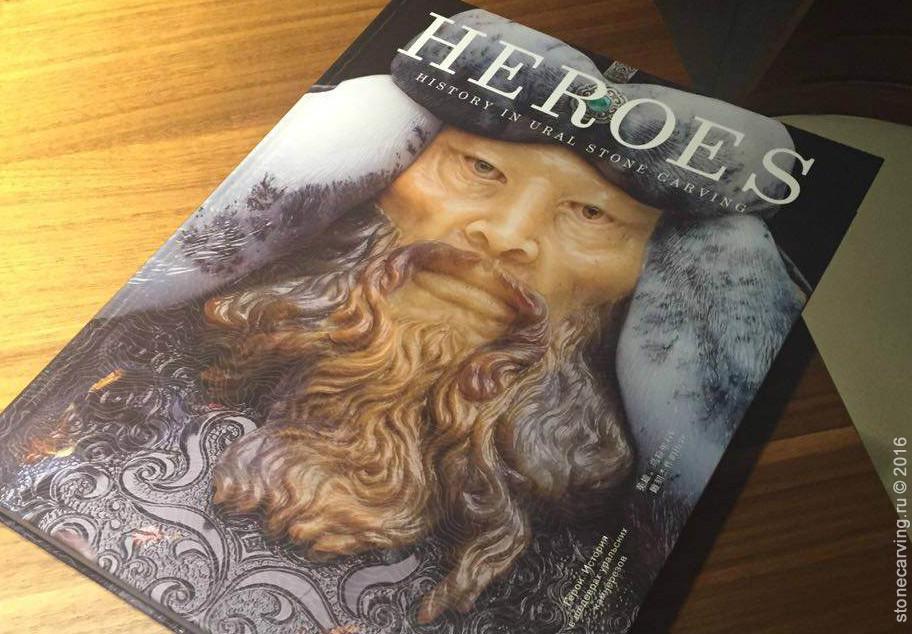

The exhibition catalog “Heroes. History in Ural Stone Carving” is published

The book is prepared specially for the exhibition, which opened on 23 of March in Liechtenstein National Museum: the reader will find all stone sculptures presented in the exhibition in the catalog.

Exposed stone compositions

August 25, 2015 — The ‘Exhibition’ section provides all stone carving compositions, forming the Legends and Fairy tales in Ural stone carvings exhibition.

New exhibition opened in Vaduz on 8 July

July 8, 2015 — The opening ceremony of ‘Legends and fairy tales in Ural stone carvings’ exhibition took place on 8 July in Liechtenstein National Museum.

Legends and fairy tales in Ural stone carving

The Legends and fairy tales in Ural stone carving exhibition showcases the best hard stone sculptures dedicated to fairy tales, mythological figures and epic heroes. Folklore has always been part and parcel of Russian culture — from ancient times to the modern day. Writers and artists find inspiration in folk tales and the Russian language itself is full of references to stories and images that are well known to Russian people from early childhood.

Five Centuries of Three-Dimensional Mosaic

The history of stone carving in the Urals dates back to the time when Peter the Great was reforming Russia. Over the three hundred years of its existence, this art has changed but it has always had surprisingly close ties with Western European practices in stone-cutting.

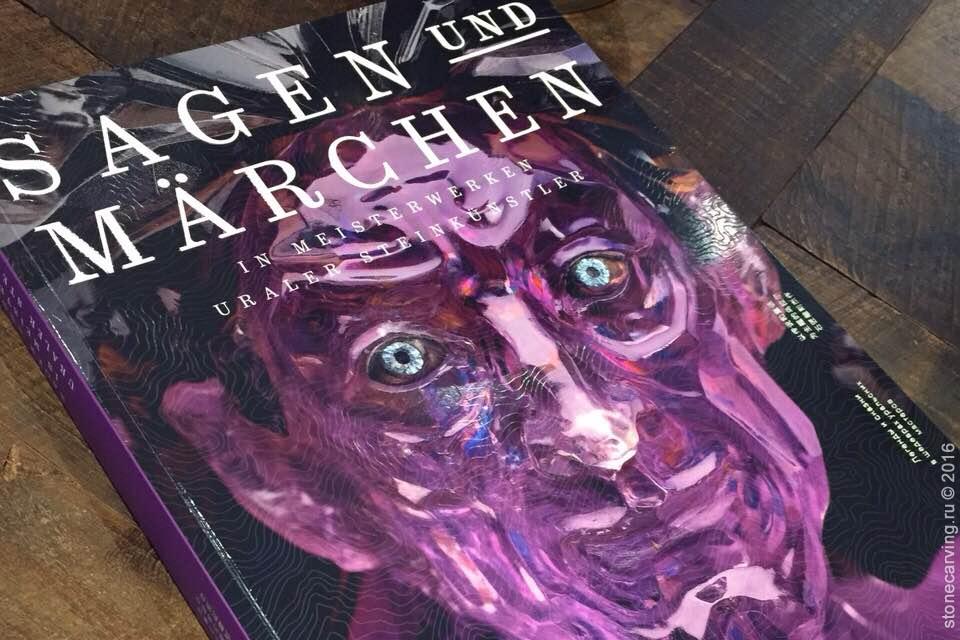

The book about stone carving picked up European award

“The Best Books of Liechtenstein 2015” award was given to the book “Legends and fairy tales in Ural stone carvings”

Stone sculptures: creation

Roomple Internet video channel had visited the ‘Svyatogor’ workshop and made a film about the process of creation of stone sculptures by stone carvers.

The catalogue of ‘Legends and fairy tales in Ural stone carvings’ exhibition is available

July 6, 2015 — The catalogue in four languages will be available in Liechtenstein National Museum in Vaduz.

Hard stone carving in the Urals: a story with a new beginning

Hard stone carving developed intensively in the 18–19th century and the active exploration of the Urals — one of the most unusual Russian regions, rich in unique gems — played an important role in this process. The Ural Mountains, which gave the region its name, divide Europe and Asia and behind them lies vast Siberia. Historically, the development of this region has been linked with mining and naturally, such a diverse range of minerals and rocks generated a lot of interest in the art of hard stone carving.