Five Centuries of Three-Dimensional Mosaic

The history of stone carving in the Urals dates back to the time when Peter the Great was reforming Russia. Over the three hundred years of its existence, this art has changed but it has always had surprisingly close ties with Western European practices in stone-cutting.

The history of stone carving in the Urals dates back to the time when Peter the Great was reforming Russia. Over the three hundred years of its existence, this art has changed but it has always had surprisingly close ties with Western European practices in stone-cutting. While it is true that the craftsmen in the Urals adopted technology, borrowed some elements of style, shapes, and individual techniques, they were trend-setters as well. In the first half of the 19th century, two generations of the Demidoffs, owners of factories and mills in the Urals, took Europe by storm with the Ural malachite. Some time later, in the middle of the century, people who were at the head of Prussia and the Vatican were charmed with the splendour of rhodonite carvings from Yekaterinburg. Both the public and their European competitors appreciated the works by the skilled craftsmen. To mention but a few examples, Russian entrepreneurs brought pieces made of two types of clear quartz (rock crystal and smoky quartz) and a unique “still life with fruit” carving on a blotting case to display at international exhibitions.

Three-dimensional mosaic became the last European method for working with coloured stones mastered by craftsmen from the Urals in the declining years of the Russian Empire. The challenging technique of creating a sculpture out of multiple pieces carved from different stones one by one opened new opportunities for the masters. No matter what twists and turns the Russian history took throughout the 20th century, they have preserved the art and have kept it alive. As the new millennium begins, one hundred years after it first made its way to Russia, three-dimensional mosaic is having its day again. It has been a long and rocky road from that time to now, taken and passed by several generations of artisans. To appreciate the distance covered, we will need to look at the ups and downs in the history of this method in Europe, and to find out who first turned to this art in Russia and how masters in the faraway Urals maintained the tradition and revived interest in multi-coloured carved stone sculpture.

At the Roots

The history of European sculpture clearly demonstrates that for thousands of years this type of art sought to convey the image of a model in a realistic way. Only the modern age saw monochromatic patterns of three-dimensional works of art, and conventionality arising from such patterns. At earlier stages, artists created picturesque design of sculptures by joining together pieces of different kinds of coloured gemstones. Examples include monuments of lost civilisations of Ancient Near East and Ancient Egypt. In late Antiquity, this techniquebecame a frequent practice — thus, busts with the head and the clothing carved of different stones, were highly popular in Rome in the period of the Antonines’ rule (2nd centuries AD). A vast collection of antique pieces of coloured stone mosaics was kept in the Villa Borghese. Part of the collection was sold to the Louvre in 1807. The Moor sculpture is a vivid example of a combination of alabaster, coloured marble, and lapis lazuli in one piece.

In later periods, the complex technology used for carving and the high cost of material for commesso (the term used by Italian masters referring to three-dimensional stone mosaic) led to the almost complete disappearance of this art. In the Middle Ages, multi-coloured sculptures and reliefs were made of tinted wax, painted wood or painted stone.

Artists turned to the ancient method of colouring sculptures once again at the end of the 16th century in Italy, in the late Renaissance.

|

|

Maure. Rome, early 17th century. Collection of Musée du Louvre, Paris PHOTO © MUSÉE DU LOUVRE, DIST. RMN-GRAND PALAIS / DANIEL LEBÉE / CARINE DÉAMBROSIS |

The Renaissance. 16th Century — Early 17th Century

The rulers of the Florence in the Renaissance had a particular passion for ornamental stones. Lorenzo the Magnificent laid the foundation of the collection of antique and new cameos. Cosimo I enriched the collection by pietra dura (hard stone) vases made by the Grand Dukes’ court artists (botteghe granducali).

The Miniature Altar created in 1590–1598 can be named as the earliest example of three-dimensional Florentine mosaic. It is decorated with mosaic scenery and three-dimensional figures of Christ and the Samaritan woman made of precisely fitted cubes of multi-coloured jasper, agate, and amethyst.

|

|

Galleria dei Lavori, probably after a design by Francesco Mochi. Saint Mark. (c) Gabinetto Fotografico Del Polo Museale Regionale Della Toscana |

At the turn of the 18th century, the Grand Dukal workshop conceived a grand project of the altar for the family church of the House of Medici. The idea was to create a marble structure of several levels, and to crown it with a rock crystal hemisphere resting on columns, planes, and niches of the same material, and to decorate it with three-dimensional mosaics and a sculpture in the round made of coloured stones. The implementation took longer than planned, for even with the improved carving technique the masters could not tool the tesserae made of various types of solid jasper and quartz quickly.

Two generations of the Mochi family — Orazio and his sons Stefano and Francesco — worked on the figures of the Apostles for half a century. Today we know about eight sculptures made for this altar using the three-dimensional mosaic technique: Luke, John, Mark, Matthew, Peter, Paul, James and an Archangel. All figures are of the same height (about 32 cm), are rather big, and were designed in the same manner: the sculptures portray standing barefoot people with false hair, dressed in long robes and wide draped cloaks made instones of contrasting colours.

This ambitious project was never completed due to financial and technical problems. However, it had a great influence on the Florentine craftsmen. At the beginning of the 18th century, two reliquaries were produced in the Grand Dukes’ Studio under the supervision of Giuseppe Antonio Torricelli (1662–1719) — the Reliquary of Dominican Saints and the Reliquary of Saint Fathers the Founders. These small structures are shaped as hexagonal towers crowned with rock crystal domes resting on twisted crystal columns. Mosaic sculptures of saints are placed in the niches.

|

|

Galleria dei Lavori, by Giuseppe Antonio Torricelli. Reliquary of Saint Emerico. (c) Gabinetto Fotografico Del Polo Museale Regionale Della Toscana |

The mosaic relief technique spread from Italy to Prague, the main residence of Rudolph II, the Holy Roman Emperor. Ottavio Miseronis (1568–1624), an outstanding carver, worked at his court in the late 16th through the first quarter of the 17th century. Concentrating on small-scaled works — a kind of coloured cameos — he created miniatures marked by the rare beauty of the Bohemian stones used. Mary Magdalene (circa 1610) is rightly considered to be the most significant piece created at that time. The subtle palette consisting of more than fifty pieces uses the colour nuances of a dozen varieties of agates and jaspers. Even though no specimen of mosaic sculpture in the round have survived, the Prague workshop showcases one of the earliest examples of the Florentine craftsmen’s technique mastered elsewhere in the world.

Development. 16th Century — Early 17th Century

In the second half of the 17th century, Christoph Labhardt (1644–1695), a master of the lapidary craft, worked at court of John, Count of Nassau-Idstein. In 1671–1679 he created a monumental mantelpiece composition commissioned by the Count. Using a complex Baroque style combination of flat, relief, and three-dimensional mosaics, the craftsman materialises the admonition that the Duke wished to convey to his son George Augustus. A didactic allegoric scene unfolds against the background of a landscape with an architectural motif set in theFlorentine mosaic technique with some relief elements (clouds, columns). Virtues of a wise ruler (female figures of Prudence, Modesty, Justice, Piety, Generosity, Diligence, and Art and History accompanying them) surround the young rider on a rearing horse. They are embodied in sculptures that have almost no relation with the pedestal. Vices carved as bas-relief are shown in front of them, as if moving deep into the composition. This is the only large work of art outside of Italy designed in accordance with a complex plan. Various types of jasper, chalcedony, and agate from deposits of Central Europe were used in it.

|

|

Christoph Labhardt. Chimney Piece. Idstein, between 1671 and 1679. Collection of Staatliche Kunstammlungen Dresden (C) BPK - Bildagentur für Kunst, Kultur und Geschichte, Berlin |

In the Baroque period, under Duke Cosimo III, the role of sculptors who worked in the Florentine court workshop became more prominent again. The complexity of the models they created increased, which made the value of “relief” mosaics higher as compared to that of flat mosaics. The foremost artists working at the studio, Giuseppe Antonio Torricelli, the carver, and Giovanni Batista Foggini (1652–1719), the designer, were the trend-setters in the inlay sculpture development during that period. In collaboration, these two craftsmen produced numerous reliquaries and other religious objects commissioned by the Duke. In the first quarter of the 18th century, this artistic tandem designed and produced a reliquary of St. Mary of Egypt (1704), and a reliquary of St. Ambrose (1705). The complex composition of the reliquary of St. Pietà (1717) includes a mosaic relief image of Pieta and a sculptural image of St. Emeric himself. The eye rests upon the bright variety of the stone palette (red Bohemian agate, Persian lapis lazuli, a cloak of yellow Sicilian jasper lined with Saxon quartz intersticed with pieces of amethyst), and on the decoration using precious stones, which is unusual for earlier works by the Florentine craftsmen: edges of the garments, tops of the shoes, and the sword are bejewelled with rubies and diamonds set in gold.

The sculptures of Roman emperors created in the first half of the 18th century in Frankfurt on the Main, where Johann Bernhard Schwarze(n)burger (1672–1741) worked, are also distinguished by rich decor. His workshop made mosaic sculptures of legendary emperors, such as Titus, Caesar, Domitianus, and Vespasianus. In his works he used coloured stones of the Hunsrück mountain range where Idar-Oberstein, one of the largest European stone-carving centres, is situated. In 1730s, this series became part of the collection of the Elector of Saxony.

The works dating back to the first half of the 18th century were clearly influenced by the blooming Baroque: the accented decoration of gold and precious stones adds extra shine, increasing the fragmentation of the works and turning them into a universal and remarkable embodiment of wealth. It is also worth noting that at this time the range of subjects expands significantly as mythological and historic images complemented the religious theme that had dominated the works of the previous century.

Starting from the middle of the 18th century with its gallant style, three-dimensional sculptures made of coloured stones became less popular, giving way to multi-coloured bas-relief compositions on tobacco box covers. Saxony became the production centre for such items, which affected the mineralogical composition of these mosaics. Though boxes with floral design prevailed, one could also find those decorated with scenes of everyday life. They are dated as far back as the 1770s, and were allegedly conceived by Heinrich Gottlob Lang (1739–1809).

We can find a peculiar interpretation of the Ancient Roman and the Renaissance Florentine inlay sculpture traditions in the composition “Rome” housed in the Louvre. The piece was created in 1785–1788 by Roman silversmiths Luigi (1726–1785) and Guiseppe Valadier (1762–1839). Over time, some of the elements were lost, such as the agate cameos with their silver frames decorating the pedestal of the composition, or the lapis lazuli ball that the figure’s hand was holding. The part of the figure that survived, clothed in a toga of Egyptian porphyry, with chalcedony arms and head, can only serve as a reminder of the attempt to breathe a new life into the complex and expensive technique.

|

|

Johann Bernhard Schwarze(n)burger. Empreror Domitianus. Frankfurt am Main, shortly before 1729. © BPK — BILDAGENTUR FÜR KUNST, KULTUR UND GESCHICHTE, BERLIN |

The Comeback. Late 19th Century — Early 20th Century

In the middle of the 19th century, as attention turned to the past eras, bright colours became a welcome element in the interior design once again, and the interest for the art of small-scale three-dimensional sculpture returned.

Contrary to many other places in Europe, the court studios in Florence still worked actively, even with all changes and many new rulers that the history of this city saw in the 19th century. Niccolò Betti, the manager of the studio known as Opoficio delle Pietre dure, decided on what kind of orders the artists would take and what trends they would follow in the last years of the Grand Duchy of Tuscany up to the year 1876. The long-forgotten tradition of relief and three-dimensional mosaic became popular again in the final period of Italy’s unification (1861–1871). Paolo Ricci (1835–1892) created the first Florentine inlay sculptures of the 19th century. The artist who worked in Opoficio delle Pietre Dure since 1855, preferred the more laconic style of mosaic sculptures of the early 17th century to Torricelli’s Baroque splendour. He used this technique for his mosaic reliefs and round sculptures. The bas-relief “Christ Praying in the Garden of Gethsemane”, which was presented to Pope Leo XIII in 1870, has survived to this day. Ricci exhibited the inlay figure of Cimabue at the International Exhibition of 1873 in Vienna. Then, three years later, he created the sculpture portraying Dante as an Ambassador to Boniface VIII. Around 1880, the studio began working on a “Liberated Italy” mosaic sculpture in commemoration of the annexation of Venice.

|

|

Georges Lemaire. Etienne Marcel. Paris, 1914 PETIT PALAIS / ROGER-VIOLLET |

It is worth mentioning that young Carl Fabergé spent a few months in Florence exactly at that time — in the middle of the 1860s. He visited the capital of Tuscany as part of a long trip he took in order to see outstanding works by European jewellers and carvers. Later, he tapped into the knowledge and experience he gained in Dresden, Paris, Frankfurt, and London to develop the special style of the items produced by the Fabergé family company.

Ricci was not the only Florentine craftsman who produced multi-coloured items of different coloured stones at the turn of the 20th century. The sculptor Aristide Petrilli (1868 – after 1907), a graduate of the Art Institute, and an Honorary Member of the Florence Academy of Art since 1898, made extensive use of mixed materials. Thus, he displayed “The Bust of Joan of Arc” made of white marble with gilded bronze parts at the International Exhibition in Paris in 1900. Some small sculptures and sculpture compositions on columnar pedestals made of variegated marble, rock crystal, lapis lazuli, and malachite dating back to the late 1890s and the 1900s are also known.

The artists’ trips, international and academic exhibitions sparkled a new interest in three-dimensional mosaic that quickly spread beyond Italy.

As early as in 1881, Auguste Alfred Vaudet, a French carver and sculptor (1838–1914) exhibited a small “Bust of Ajax” at the Salon of French Artists. Raised on a jade column, it featured a conventional selection of stones and free treatment of colour: the red-brick jasper helmet and the bright lapis lazuli clothing rested on the bust carved from dark green jasper.

Another example of the French approach to three-dimensional mosaic is known only by description and an old photograph reproduced in the book published in the early 20th century. Relief “Into the Unknown” by Emile Félix Gaulard (1842–1924), a French cameo craftsman and designer, was exhibited at the Salon in 1902. The composition was set in bright sardonyx, bloodstone, Hungarian opal, and Ural blue chalcedony.

Georges Henri Lemaire (1853–1914), better known as a carver and a portrait medallist, was the most consistent in using three-dimensional mosaic in France. In 1890s — 1910s, he created several inlay sculptures in coloured stones. While in his early works he used one material for the “main body” of the sculpture and only used a different one for hands and heads, his piece produced in the later period of his artistic career — the Etienne Marcel sculpture — features a broad variety of elements, creating bright pieces of his character’s clothes.

Russia. The Early 20th Century

Close links between European and Russian arts and crafts, as well as cosmopolitan tastes of Russian customers, were the reason why Russian carvers tried their hand in the art of three-dimensional mosaic. If we recall the interest of Carl Fabergé in various techniques and materials, it seems quite natural that he established an “in-house” lapidary workshop in his own company. Peter Kremlyov (1888 — after 1937) and Peter Derbyshev (1888–1914), graduates of the Yekaterinburg School of Art and Industrial Design, were its most valuable employees. In the late 1900s, they produced their first figurines. These figurines were later included in the series known as “Russian types” (a street cleaner, a shoveller, a coachman, a horse-cab driver, etc.). As mosaic sculptures became more and more popular with the customers, the range of products grew — the workshop could offer anything from individual typical images and portraits of people who could be seen in the streets of the capital and in the imperial court to sophisticated genre scenes, and characters of fairy tales and jocular images depicting national stereotypes. More than fifty figurines made by the Fabergé Company in 1908–1916 are known. Most of them are made according to the tradition developed in Europe — a combination of fairly large elements made of stones in contrasting colours gives the image an ornamental touch. The main difference can be seen in the way the eyes are interpreted: the Fabergé workshop encrusted them with faceted gems, while European masters used carving or realistic inclusions of ornamental stones. The height of the sculptures is also different — 10 to 20 cm in the case of the items made in St. Petersburg, as compared to the figures of the Apostles and the Roman emperors that are about 30 cm tall. The approach to accessories of precious metals is similar to that used by Schwarze(n)-burger: all kinds of accessories (weapons, buttons, and imitation of sewing and metal decorations) are made of gold and silver, sometimes with enamel decor.

|

|

The House of Fabergé. Kamer-kazak N.N. Pustynnikov STAIR GALLERIES, NEW YORK |

Alexey Denisov-Uralskiy (1864–1926) was the only one who could rival Fabergé’s sophisticated works using this intricate stone carving technique. The first products by his workshop, where he combined elements in different stones in one sculpture, were figures of birds. Denisov-Uralskiy used these skills to create an extensive series of “Allegorical Figures of the Belligerent Powers”, which included fifteen sculptures, in 1915–1916. Twelve sculptures represented the countries involved in the conflict (Russia, France, Great Britain, Italy, Serbia, Montenegro, Belgium, Japan, Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria, and Turkey), and three other sculptures were of descriptive nature. Some of the allegories were represented in the form of multi-coloured sculptures. These include Austria, France and the “Monument to William”, the most complex image in terms of composition formula. Despite the lack of information about other inlay figures made by the Denisov-Uralskiy’s workshop, we can draw some conclusions about the interpretation of this technique. Unlike his competitor, the Fabergé company, the craftsman from the Urals rarely used metal, and the stone played the main decorative role, just like in the Florentine works.

The Urals. Keeping the Tradition Alive. The 20th Century

With the changes in the market caused by the First World War and the October Revolution that followed, workshop owners in the capital lost their business. The stone cutters were forced to look for new jobs or to return to where they came from, hoping to find jobs in their field in the provincial towns where the atmosphere was much calmer. Peter Kremlyov, ex-manager at the Fabergé’s stone carving workshop, returned to Yekaterinburg. Soon, however, he left for the area today known as the Perm Region to work in soft stone mining.

The carved pieces produced between the First and the Second World Wars were usually made to less costly prototypes, which, however, allowed the stone carvers to practice, whatever happened.

|

|

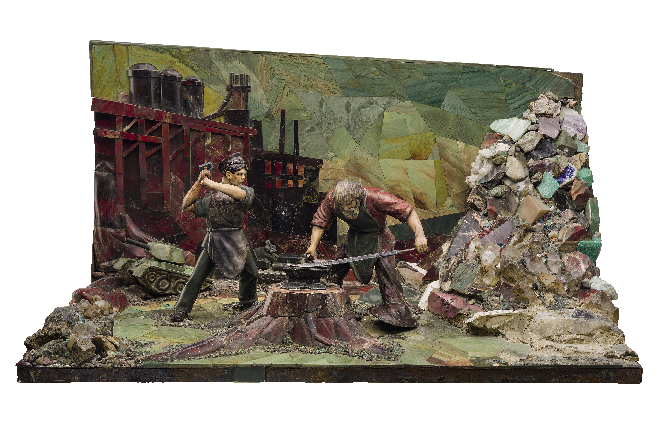

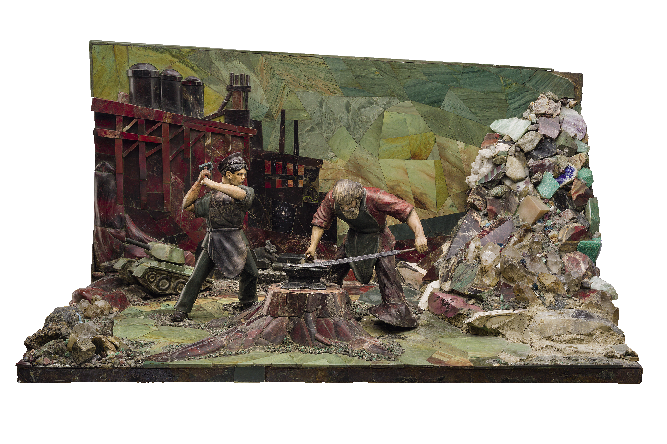

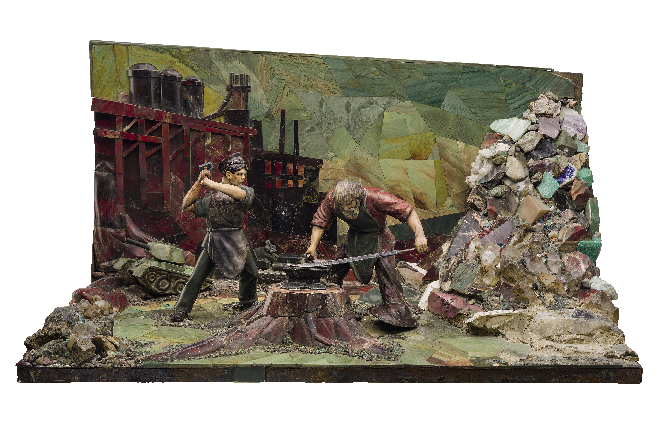

Nikolay Tataurov, students of the vocational art college No.42. The Ural Forging Victory. © EVGENY LITVINOV / ZOOM ZOOM FAMILY |

The art was given a new life after World War II. The process was initiated at a local college in Yekaterinburg — then Sverdlovsk — known as Vocational Crafts and Engineering School No.42 that had just been established then. Nikolai Tataurov (1887–1959), one of the oldest workers at the Russkiye Samotsvety (Russian Gems) factory, was among the artists who were invited to teach. He had been a worker since 1898 — when he was only eleven, he was allowed to do the first simple jobs at the Yekaterinburg Imperial Lapidary Factory. He was among the masters who worked on such outstanding monuments of Russian stone carving art as the mosaic map of France made in Yekaterinburg in 1898–1900 and the “Socialist Industry” map produced in Leningrad for the country’s display at the International Exhibition of 1937 in Paris. We have no information on the inlay pieces made by Nikolai Tataurov before the 1940s, but we can assume that he was aware of this technique and had seen items created with it. The first students at School No. 42 produced the composition “Ural Is Forging Victory” under the supervision of the master in 1948. Two figures of workers made using the three-dimensional mosaic technique are in the centre of the complex monumental composition with the background covered with beautiful flat mosaic and the bottom decorated with reliefs.

“The Little Humpbacked Horse” chest made by Viktor Sargin, then a student, in the mid-1950s, is another evidence of the fact that the traditions of three-dimensional mosaics using various stones pieced together were preserved. Relief mosaic compositions inspired by Russian fairy tales are clearly visible against the red-brown jasper on the walls: the old man throwing his fishing net into the lazuli waters, and the little boy Ivanushka (the “pet name” derived from Ivan) picking a feather from the Firebird’s tail. The skilful workmanship won the college a medal at the International Exhibition of 1958 in Brussels.

After Nikolai Tataurov passed away, local masters took up the work he started. Graduates of some of the top colleges and universities in the Soviet Union joined the teaching staff. Thus, Vladimir Rysin, a graduate of the Moscow School of Art, taught in Sverdlovsk for many years. For several decades, the works by his students were marked with the highest awards for their quality workmanship. In 1968, a sculptural group named “Danila the Craftsman and the Copper Mountain Queen” using the three-dimensional mosaic technique was produced under his supervision. The students used a subtle play of colour gradations — from reddish-brown to green — in the piece of jasper that the Stone Flower, the centrepiece of the composition, is made of. The red notes are accentuated with the bright craftsman’s shirt of wax jasper and the green hue forms a tender duet with the jade dress that the Queen is wearing.

Before the end of the same year, “Tayutka’s Mirror. Inspired by Pavel Bazhov’s Tales” piece by Vladimir Rysin’s student Nadezhda Sukhacheva (born in 1949) was awarded with a medal of the National Exhibition of Economic Achievements (VDNKh).

Nadezhda Sukhacheva has worked at the School since 1974, teaching new generations of the Ural stone carvers. Her students went on to become Members of the Russian Union of Artists or managers of well-known workshops. Thousands of works in three-dimensional mosaic have emerged from their students’ hands. This clearly demonstrates that the Ural school of stone-cutting is alive and students can learn this intricate stone-cutting technique.

The exhibition displaying several compositions created by Vassiliy Kovalenko (1929–1989), that was held in Moscow in 1973, had to a certain extent pre-determined the popularity of three-dimensional mosaic among the Ural craftsmen. Vassiliy Kovalenko, a stage designer, became interested in stone carving while working on the ballet “The Stone Flower” by Sergei Prokofiev at the Sergey Kirov Opera House (as the Mariinsky Theatre in St. Petersburg was known then). Being fascinated by the shape and pattern of stones, Kovalenko made several trips across the country as a member of the geological field parties, and visited the Urals many times. Even his first works were marked with his unique style, with the grotesque images, the peculiar dramatic interpretation, and multiple figures. Kovalenko’s sculptures are different from earlier works by Ural craftsmen in the mid-20th century in that he uses a greater variety of stones and numerous accessories made of metal.

|

|

Vladimir Rysin, students of the vocational art college No.42. © EVGENY LITVINOV / ZOOM ZOOM FAMILY |

The Urals. Comeback. Late 20th century — Early 21st сentury

One cannot overestimate the impact made by the return of Fabergé’s works as they took their rightful place in publications and displays. The items re-discovered include the inlay figurines that had been stored in museum vaults up to a certain period in time and were onlyknown to a narrow circle of experts. The first exhibitions of these objects (1989–1992), which coincided with a dramatic change in the country’s political and economic situation, gave a clear sign that the chain is unbroken and the traditions are alive. New opportunities for artistic self-expression free from ideological and institutional restraints of the past gave a powerful impetus for the artists to develop their style and establish a new community of the lapidary art connoisseurs. This led to a dramatic increase in the number of inlay figurinesof coloured stone shown at various exhibitions and added to private and museum collections.

Many artists spent the 1990s and the 2000s in search of their unique ways. They experimented in art and tried to adapt to the new economic context. These factors had a strong influence on the quality of their works and the choice of materials. The Ural masters started off by experimenting with individual sculptures typical for Fabergé such are the works by Oleg Alexandrov (born in 1960) produced in the early 1990s. The compositions gradually become more and more complex, with elements of decor.

While such elements had already been present in some of the works in the 1970s, they became almost a must in 2000s. The trend is typical for both the older masters (like, for example, Anatoliy Zhukov (born in 1956)), and the younger generation of artists.

|

|

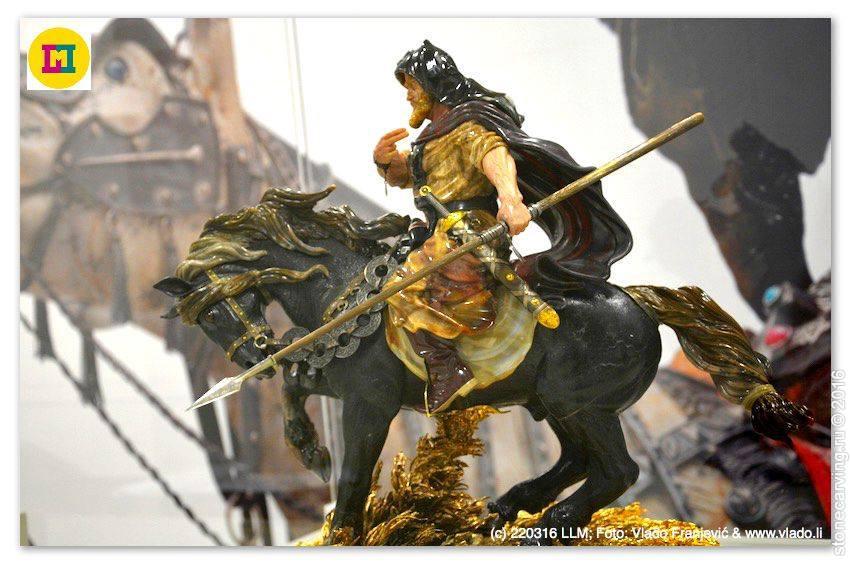

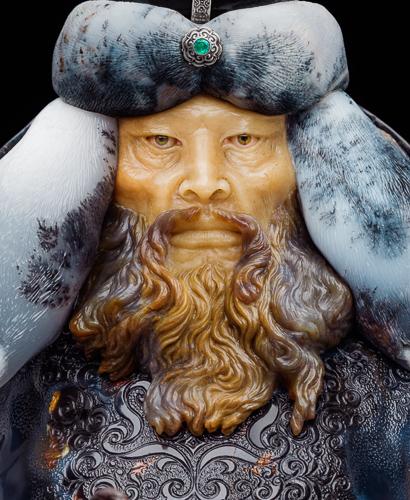

Denis Davydov and a Peasant-Guerrilla. Writing Set. "Svyatogor" Hard stone carving studio. 2012. © EVGENY LITVINOV / ZOOM ZOOM FAMILY |

The new decade is marked by the emergence of complex compositions made up of many elements. Just like in the golden age of three-dimensional mosaics in Florence, they require a lot of skill and effort from the sculptor who should be mindful of the nuances of the technique, rather than simply create an artistic image. The work is not easy, and the artist undertaking it should be skilled in different fields, which has dictated the need to set up teams. Such large artistic workshops as “Svyatogor” or “Alexey Antonov’s Workshop” employ stone-cutters, jewellers, sculptors, and designers for each piece.

As the scupltures increase in size and complexity, they show the features typical for the Ural stone carving in a new light. Back in the 19th century, the local masters “played” with the surface texture, the method that was used as early as in the mosaic sculptures by Alexey Denisov-Uralskiy who learned it from other 19th century artists. The masters used fine carving, matt surfaces, various types of satin finish, and glossy polished textures, and arranged those to achieve the desired effect.

Limited use of metals is another feature that makes works from the Urals stand out: very little gold, silver, and coated non-precious metals is used, and only where it is impossible to use stone instead. Buttonholes on caftans and uniforms, and epaulettes — the elements that are gold-threaded in reality — are made of golden-coloured tiger’s eye. Even the exclusively metal parts of weapons and armaments, such as helmets, hauberks, cuirasses, and chain armour, are cut from such unpredictable materials as pyrite and hematite, which requires delicate work.

The carvers use unique materials. They have a special passion for jasper. This material has no equals in terms of diversity of patterns and shades. The man laid his eye on the rich jasper deposits in the Urals as far back as the Palaeolithic era. Quartz, including transparent rock crystal, amethyst and smoky quartz, ornamented agate and matt chalcedony are no less popular. Layered silicon can be used to achieve a variety of effects, be it the wolf’s fur or the precious embroidery on luxurious silk. The craftsmen also make extensive use of such special stones that can only be found in the Urals as green garnet (uvarovite) or bright pink rhodonite (eagle stone).

Today the local three dimensional mosaic is having its day again. Using techniques invented by the European coloured stone carvers, absorbing the traditions of the Russian lapidary art and using new technology, craftsmen create complex dramatic images, experimenting freely with a broad range of materials.

Ludmila Budrina

PhD, History of Art; Associate Professor

References

Литература:

- Art of The Royal Court: Treasures in Pietre Dure from the Palaces of Europe. / Wolfram Koeppe and Annemaria Giusti. — New York, 2008.

- Das Historische Grüne Gewölbe zu Dresden; die barocke Schatzkammer / Dirk Syndram, Jutta Kappel, Ulrike Weinhold. — Berlin, 2007.

- Die Kunst des Steinschnitts: Prunkgefässe, Kameen und Commessi aus der Kunstkammer / Rudolf Distelberger. — Wien, 2002.

- González-Palacios, Alvar. Mosaique et pierres dures. Florence, Pays Germaniques, Madrid. – Paris, 1991.

- L’Opoficio delle Pietre Dure nell’Italia Unita. — Livorno, 2011.

- Sacri Splendori: Il Tesoro della ‘Cappella delle Reliquie’ in Palazzo Pitti. / Gennaioli, Riccardo; Maria Sframeli. — Livorno, 2014.

- «...Более, чем художник...»: к 150-летию со дня рождения Алексея Козьмича Денисова-Уральского / Будрина Л.А. — Екатеринбург, 2014.

- Будрина Л.А. Объёмная мозаика в камнерезном искусстве: европейская традиция до и после Фаберже // Известия Уральского федерального университета. Серия 2. Гуманитарные науки. 2012. № 1 (99). — Екатеринбург, 2012. — С. 6–24.

- Фаберже Т.Ф., Илюхин В.Н., Скурлов В.В. Фаберже и его продолжатели. Камнерезные фигурки «Русские типы». — СПб., 2009.

The exhibition “Heroes. History in Ural Stone Carving” has opened in Liechtenstein

The exposition is displayed in Liechtenstein National Museum

Heroes. History in Ural Stone Carving

The Opening Ceremony of ‘Heroes. History in Ural Stone Carving’ exhibition will take place on the 23rd of March at 19.00 in Liechtenstein National Museum

The exhibition in Liechtenstein has opened its doors

July 9, 2015 — The exposition welcomes everyone in Liechtenstein National Museum until 18 October 2015.

Introduction

Today we are witness to the golden age of new media. Children now turn to computer games rather than reading or listening to audio books. That is probably why this exhibition of stone sculptures based on fairy tales is somewhat surprising. The question that arises is perhaps the following: Is there still a need for fairy tales or for the art of stone carving?

Stone carving: from concept to finished work

Hard stone carving is a truly unique art. On the one hand, the stone carver is an artist and a creator, who gives a hard and shapeless piece of stone a new life and a new shape. On the other hand, his most important task is to unveil and demonstrate what has already been created by nature: beauty, structure and the unique character of the stone. When it comes to working with stone, each piece requires this fine balance between creating and being guided by the material itself.

The exhibition catalog “Heroes. History in Ural Stone Carving” is published

The book is prepared specially for the exhibition, which opened on 23 of March in Liechtenstein National Museum: the reader will find all stone sculptures presented in the exhibition in the catalog.

Exposed stone compositions

August 25, 2015 — The ‘Exhibition’ section provides all stone carving compositions, forming the Legends and Fairy tales in Ural stone carvings exhibition.

New exhibition opened in Vaduz on 8 July

July 8, 2015 — The opening ceremony of ‘Legends and fairy tales in Ural stone carvings’ exhibition took place on 8 July in Liechtenstein National Museum.

Legends and fairy tales in Ural stone carving

The Legends and fairy tales in Ural stone carving exhibition showcases the best hard stone sculptures dedicated to fairy tales, mythological figures and epic heroes. Folklore has always been part and parcel of Russian culture — from ancient times to the modern day. Writers and artists find inspiration in folk tales and the Russian language itself is full of references to stories and images that are well known to Russian people from early childhood.

Five Centuries of Three-Dimensional Mosaic

The history of stone carving in the Urals dates back to the time when Peter the Great was reforming Russia. Over the three hundred years of its existence, this art has changed but it has always had surprisingly close ties with Western European practices in stone-cutting.

The book about stone carving picked up European award

“The Best Books of Liechtenstein 2015” award was given to the book “Legends and fairy tales in Ural stone carvings”

Stone sculptures: creation

Roomple Internet video channel had visited the ‘Svyatogor’ workshop and made a film about the process of creation of stone sculptures by stone carvers.

The catalogue of ‘Legends and fairy tales in Ural stone carvings’ exhibition is available

July 6, 2015 — The catalogue in four languages will be available in Liechtenstein National Museum in Vaduz.

Hard stone carving in the Urals: a story with a new beginning

Hard stone carving developed intensively in the 18–19th century and the active exploration of the Urals — one of the most unusual Russian regions, rich in unique gems — played an important role in this process. The Ural Mountains, which gave the region its name, divide Europe and Asia and behind them lies vast Siberia. Historically, the development of this region has been linked with mining and naturally, such a diverse range of minerals and rocks generated a lot of interest in the art of hard stone carving.