Alexander Suvorov

2015

Alexander Suvorov was born into an old noble family. His father, Vasily Ivanovich Suvorov, was a General-in-Chief and a Senator. He named his son in honour of Saint Alexander Nevsky famous for his victories over Swedish and German Crusaders. In 1742, Alexander was enlisted in the Semyonovsky Life-Guards Regiment, and in 1748 he joined active service in the Regiment.

Alexander Suvorov, 1739 – 1800. Generalissimus, Count of Rymnik, Prince of Italy, was a great Russian military leader.

Alexander Suvorov was born into an old noble family. His father, Vasily Ivanovich Suvorov, was a General-in-Chief and a Senator. He named his son in honour of Saint Alexander Nevsky famous for his victories over Swedish and German Crusaders. In 1742, Alexander was enlisted in the Semyonovsky Life-Guards Regiment, and in 1748 he joined active service in the Regiment.

Suvorov participated in the battles of the Seven Years’ War (1756 – 1763), the Russo-Turkish war (1768 – 1774), and many others. His outstanding leadership talent manifested itself most vividly during the Russo-Turkish war of 1787 – 1791. In 1787, he defeated the Turkish troops near Kinburn; in 1789, he crushed the Turks in Focsani and Rymnik; in 1790, he besieged and took by storm the fortress of Izmail, formerly rumoured to be unassailable.

In 1799, Suvorov was appointed Commander-in-Chief of the Russian forces in the war against Napoleon, in which Russia was in alliance with Austria and England. He led the Italian and Swiss expeditions that were outstanding in terms of their strategic intent and heroism, traversing the Alps in the place that was considered impassable for an army. During the Swiss campaign, the troops led by Alexander

History

Suvorov fought their way through the St. Gotthard pass and via the stone Teufelsbrücke (Devil’s Bridge) and passed from the Reuss Valley into the Mutten Valley where they were encircled by superior forces of the French. Locked in “the stone sack”, Suvorov started breaking out of the encirclement, and at this time the rear guard of the Russian army inflicted a cruel defeat on the army led by General Massena. Massena was nearly captivated, and the French troops scattered. After that, Suvorov’s army broke through the hard-to-reach Ringenkopf (Paniks) Ridge, then reached the town of Chur, and at the end of 1799, they returned to Russia.Suvorov became famous not only as a great military leader but also as a warfare theorist. In his treatise “The Science of Victory” and other writings, he outlined the principles that underlay his consistent success: offensive strategy and skilful use of manoeuvre, encouragement of the officers’ initiative, affectionate treatment of the soldiers and trust in them, patriotism, service to the ideals of honour, and care for people of lower ranks. Suvorov coined the phrases that became proverbial in Russia: “What is difficult in training will become easy in battle”, “The bullet is a fool, the bayonet is cool”, and others. His legacy played a huge role in the development of Russian military thought.

The Stone

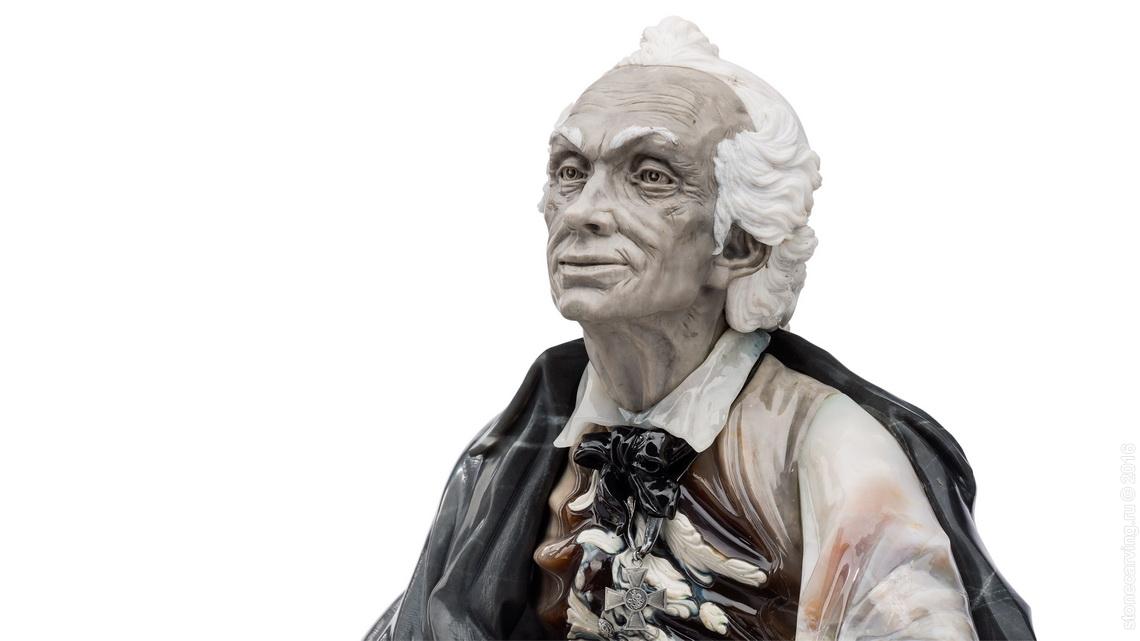

The artists created an artistic image of Suvorov, which shows in an unexpectedly monochrome design of the sculpture. By combining pieces from different materials, the artists could use the textures of surfaces and shades of grey to achieve the effect more reminiscent of a precious engraving than a multicolour painting.

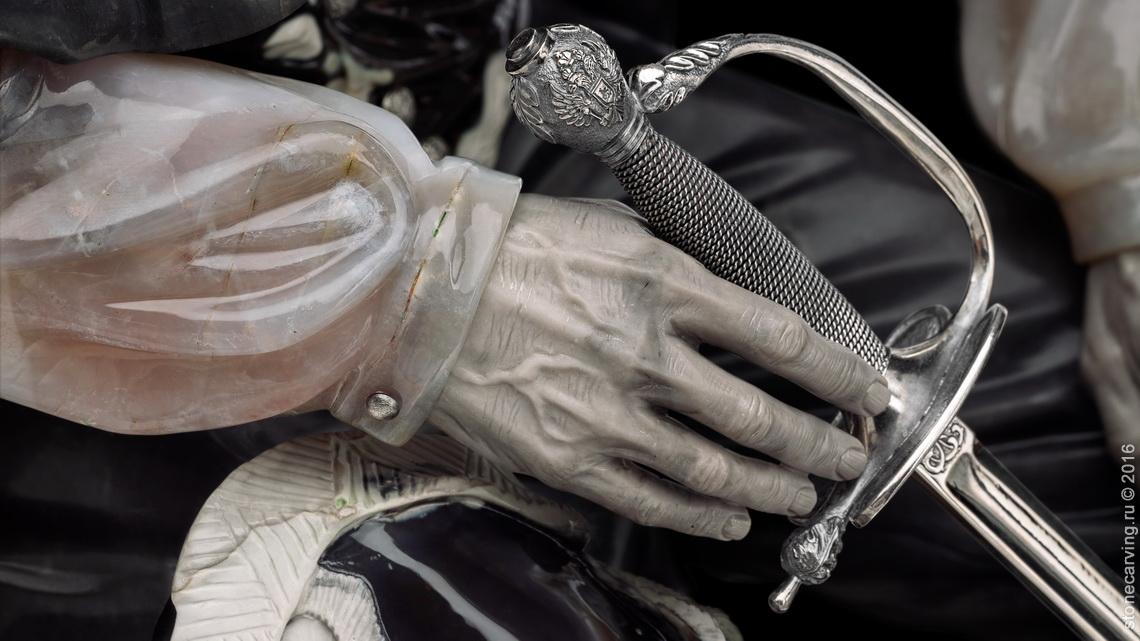

Suvorov is portrayed in a brief moment of rest early in the morning, sitting on the Regiment’s drum. The point of his unsheathed silver sword touches the ground, as if he has just sketched something with it. The cloak and the pants are made of quartzite, with varying degrees of finish, which creates the impression of different types of cloth. This play of textures is emphasized with the silk shiny surface of the shirt carved from chalcedony and the vivid play of the thick satin of the vest. The pattern on the costume was created using the cameo technique; the same technique is used for the hat with its bright decor created using layers of flint in varying shades.

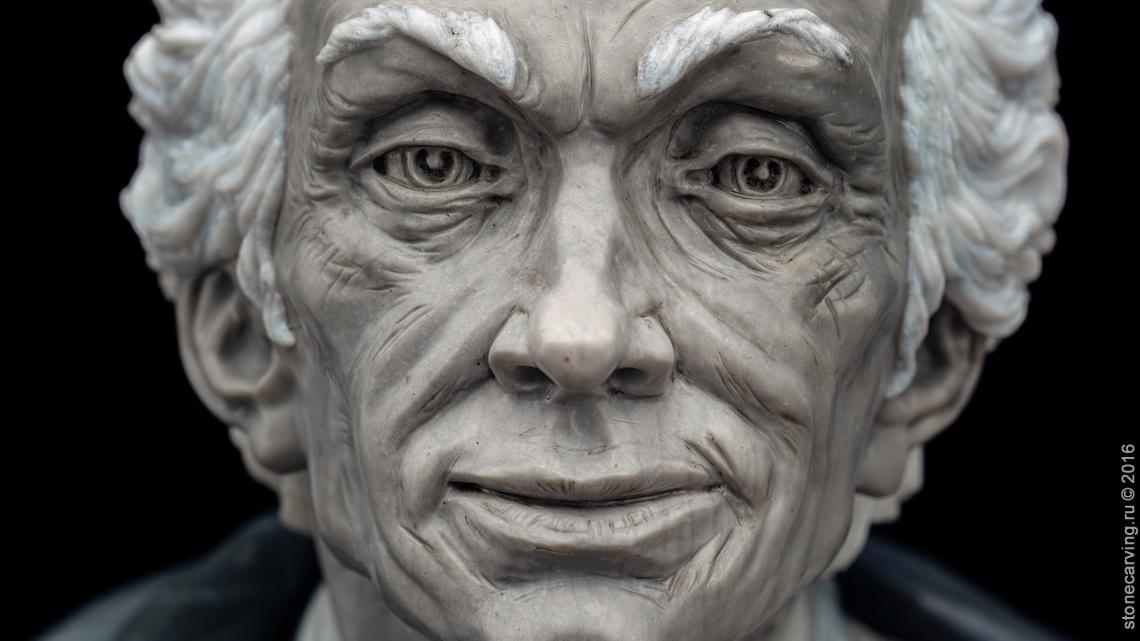

The face, elements of the costume and the drum are made of flint, and the choice of this material is logical. This stone was used in the production of armaments since ancient times (the types of products ranged from arrowheads to gun locks, remaining in use in the times of Alexander Suvorov) and in the Russian tradition, a tough, persistent person who remains committed to their decisions no matter what, is still called “flint”.

Marcillac P. L. A. de Crusy Suvorov

Suvorov possessed in-depth knowledge of sciences and literature. He liked to show how well-read he was, but only to those who, as he felt, would be able to appreciate the information he provided. He had an exact knowledge of all European fortresses, with all details of their facilities, as well as all positions and locations where the famous battles were fought. He talked a lot about himself and about his military exploits. I quote: “A man who commits great deeds must talk about them frequently to excite competition and ambition in the audience.” Possessing a military genius, he reflected on actions from the perspective of the people in the highest ranks. I have often heard the following judgments from him: “Having received the Emperor’s order to assume command of the troops, I ask him which lands he wishes to conquer. Then, I design my plan of action in such a way as to invade the enemy’s country, as far as possible, from different sides using many detachments. When meeting with the enemy, I defeat them: I leave that to the soldiers; as for the Commander, when planning his actions, he should not limit them to attacking any particular position. The enemy will essentially guard an important location; we will bypass them and even attack from the rear, and then, to counter the invasion of his country, they will have to split their forces.”

Suvorov dined at seven in the morning, and none of our delis would have praised his dinner that consisted of a few simple meat or fish dishes; instead of cake, a simple porridge (riz à la Cosaque) was served — this is a disgusting meal that others found excellent out of respect for the field marshal who diligently treated his guests to it. This was the festive meal that almost always had to be followed by a second dinner. There was no silver tableware, at least during campaigns. The dinner was a time of relaxation and friendly conversations with the host who would talk a lot but after that would immediately go to bed. He used a straw bundle as a bed and would sleep on it, wrapping himself in his ammunition cloak. After a two hours’ nap, the field marshal would work for quite a long time; than he would dine again at five p.m. — now alone; then he laid down and slept for two more hours, and finally he spent the night alternating work and rest.